THE WRITING LIFE ... Ioannis GATSIOUNIS

IOANNIS GATSIOUNIS is a native New Yorker who has worked as a freelance foreign correspondent and previously co-hosted a weekly political-cultural radio call-in show in the U.S. He has been living in Malaysia since the early 2000s. He is the author of a new collection of stories, Velvet & Cinder Blocks (ZI Publications, 2009). He is also the author of a nonfiction book, Beyond the Veneer: Malaysia’s Struggle for Dignity and Direction (Monsoon Books, 2008).

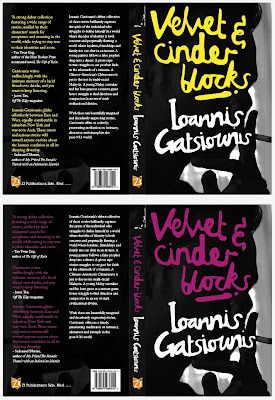

IOANNIS GATSIOUNIS is a native New Yorker who has worked as a freelance foreign correspondent and previously co-hosted a weekly political-cultural radio call-in show in the U.S. He has been living in Malaysia since the early 2000s. He is the author of a new collection of stories, Velvet & Cinder Blocks (ZI Publications, 2009). He is also the author of a nonfiction book, Beyond the Veneer: Malaysia’s Struggle for Dignity and Direction (Monsoon Books, 2008).Gatsiounis’s début collection of stories captures the spirit of the individual who struggles to define himself in a world where the idea of identity is both concrete and perpetually fleeting, a world where loyalties, friendships and family ties can alter in an instant. A young painter follows a false prophet deep into a desert. A pious rape victim struggles to see past her faith in the aftermath of a tsunami. A Chinese-American’s Chineseness is put to the test in multiracial Malaysia. A young Malay caretaker and his lone guest at a remote guesthouse struggle to find direction and compassion in an era of stark civilisational divides. With these 10 well-imagined and decadently engrossing stories, Gatsiounis offers us a timely, penetrating meditation on intimacy, alienation and triumph in the post-9/11 world.

INTERVIEW BY ERIC FORBES

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF IOANNIS GATSIOUNIS

Most readers know you for your astute writings on Malaysian politics. When and why did you turn to fiction?

Most readers know you for your astute writings on Malaysian politics. When and why did you turn to fiction?Fiction is something I’ve quietly been pursuing alongside the news analysis. Media is seductive in that it offers an immediate outlet to voice your concerns. But it’s not well suited to explore how relationships between individuals and communities play out against the backdrop of the larger world. And I was finding post-9/11, post-Iraq that those two realms—the personal on the one hand, and the external, which has become increasingly politicised—were growing inextricable. Fiction was better suited to explore that relationship.

Do you then feel contemporary fiction must be political to be relevant?

Not necessarily, though I do think it’s harder not to be in the post-9/11 world. Take, for instance, converting to Islam for the right to marry a Muslim. A choice that a few years ago may have seemed innocuously personal, today contains a polarising political dimension. And this is the case involving a whole range of issues. So, yes, politics has an important role to play in contemporary fiction.

Some of these stories—“The Guesthouse,” “Above the Merciless Waterline” and “Fathers”—seem intent on communicating the idea that people can rise above those differences.

Precisely! Nothing is inevitable. In that way the collection is very optimistic. But it is also mindful not to gloss over starker realities of our time. Events of the external world—dramatised by an ever more invasive media—are perpetuating misunderstanding. How is this happening? I was intrigued by that question.

Several of the stories suggest that intimacy is at stake?

Several of the stories suggest that intimacy is at stake?More basically, compassion. We see that in “The Guesthouse,” between Si and Basel, and later with Azara. And then in “Above the Merciless Waterline” between Hana and Putono. But not everything about the collection is political. Several of the stories deal with failed relationships that have no political connection.

Are you a pessimist on matters of intimacy?

I wanted to stress different sides of the intimacy equation. So often in film or literature a character has some void in his or her life and intimacy comes around to save the day. But life doesn’t usually work that way. Real intimacy is elusive; much of who we are is shaped in its absence. Sometimes for the worse, and sometimes for the better.

The closing novella, “The Guesthouse,” is among the most ambitious, and ultimately most inspiring, stories in the collection. What are you trying to convey?

How global events can feed our sense of limitation. More specifically I was interested in the historical moment between 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq. It’s a period that shaped the planet in unprecedented ways, but which most literature, for whatever reason, has neglected. The story is not intended as a “tour” to a foreign country. It does not exoticise; it does not get caught up in all those touristy details; it doesn’t introduce you to italicised words to give the false impression of real writing. It is concerned with detail of another sort: the effects of isolation in an increasingly connected yet politically polarised world. Through each other and their satellite channels, Si and Basel think they’re seeing more of the world when in fact they’re seeing less.

Karaoke plays an interesting role in the novella. Why? [Laughs.] Karaoke here is a metaphor for the insidiousness of conformity; inventiveness and novelty are still very much frowned upon in this part of the world. Like many Malays I’ve met, Basel is full of this buried creativity, that if unleashed could save him from his inner doubts and demons—which here have been known to work their way through race and religion. But that catharsis won’t happen if he does what is expected of him, by his own race or the other races. Karaoke is a symbol for that struggle—the struggle for creative freedom and personal responsibility.

Your stories discuss identity and belonging, among other issues. There also seems to be a recurring theme on absent or failed fathers. Could you elaborate a little about these themes?

Your stories discuss identity and belonging, among other issues. There also seems to be a recurring theme on absent or failed fathers. Could you elaborate a little about these themes?My first teachers in Montessori were Lebanese and my family would have dinners at their house. So I grew accustomed to Middle Eastern cuisine almost as early as I did American and European food. My middle and high schools were predominantly Jewish. My mother’s side of the family was made up of quintessential, assiduous, Anglo-Protestant Americans. This liberated me. I didn’t feel bound to one group or another. But the world likes its people in categories, and is suspicious of people it can’t fit into them. This really struck me during my first road trip beyond America’s East Coast. By the time I reached Kentucky it was pretty clear I was the outsider in my own country: the dark-haired, dark-eyed guy driving a Japanese car, with a Greek name. And yet I wasn’t raised around Greeks. I was American as far as I could tell. Later, as you know, I would find myself in Malaysia, where identity is a preoccupation to the point virtually of being a neurosis. The issue of identity has seemed to follow me wherever I go.

As for the theme of absent fathers, well, I’m interested in how people cope with absence. That was part of it. And part of it derived from personal experience; my father wasn’t always around. Though to be fair, he was a loving man, and I have fonder memories of him than many of my characters have of their fathers.

What do you think of the health of the short story? Do you think it’s in danger of falling into obscurity?

It is, but it’s not fated for obscurity; it’s the writer’s job to give it new life and the reader to rediscover what’s in it for them, both in terms of entertainment and understanding. Stephen King argued in a New York Times op-ed a few years ago that too many writers are writing for other writers. They’re aiming to show off rather than entertain; they’re self-conscious instead of being open. I think he’s right. Many writers have been conditioned—through MFA programs or a desire to please editors—not to part with conventions of the form. All of this has made the short story stale. In the end, it’s very important to do it your own way.

Part of the blame for the short story’s demise, too, rests with the reader, who in our media age of reason naively assumes that knowledge comes primarily if not only from facts, which they associate with nonfiction. They’ve failed to understand that what fiction’s good at—describing how people think and respond to their environment—is a fact of a different sort, and just as vital to grasp. We’ve lost touch with a fundamental truth: that one can’t truly be civilised without reading literature—that everyone from our leaders down to our neighbours would possess greater understanding and compassion if they did. But there is hope for literature, and by way the short story. In fact, the short story is a good fit for our chaotic media age. Unlike the novel, you can get in and get out. Furthermore, it can serve as a great introduction to literature. I have a friend here in Malaysia who didn’t read literature before we met. I threw a few novels her way but very quickly they’d end up back on the shelf. Then I encouraged her to read a short story by T.C. Boyle. Now without prompting she reads Boyle, Richard Ford and Annie Proulx—for fun! And I have a hunch she’s now a fuller, happier person for it.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home