CONTEMPORARY BRITISH FICTION

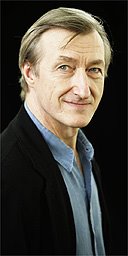

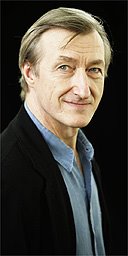

CONTEMPORARY BRITISH FICTION at its best. That’s what the works of

Julian Barnes promise to those of us who enjoy fiction that is full of satire, irony and intelligence.

His Booker Prize- and IMPAC-shortlisted novel,

Arthur & George (2005), is a beautifully realised piece of historical fiction, though based on a real-life event: it’s elegant in construction and witty and humane in execution, similar to all his other novels, short stories and essays. Those with a predilection for gentle British social satire should find his Booker Prize-shortlisted novel,

Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), delectable; it remains his best-known work. There’s much irony, quirkiness, subtlety, depth, dry humour and wit in his writing.

Critics often find

Barnes less clear-edged, less defined, compared to other British male novelists of his generation on the literary stage of contemporary Britain, especially writers like

Peter Ackroyd,

Martin Amis,

Ian McEwan,

Salman Rushdie,

Graham Swift and

Kazuo Ishiguro. According to one British critic,

Barnes “lacks a signature trait like

Martin Amis’s laddish slapstick or

Ian McEwan’s deadpan perversity or

Salman Rushdie’s magic-realist flamboyance or

Kazuo Ishiguro’s coy poignance.

Barnes is more changeable, more like the weather, and that, in the end, may perhaps be the best qualification to write the Great English Novel.

Arthur & George is finally about how Englishmen protect themselves from the heaviest emotional weather, what hard, lifelong work it is just to keep out the chill and the fog.” Despite its sluggishness and lack of depth,

Arthur & George still makes compulsive reading, and I think it is one of his best books. The narrative is irrefragably compelling and well controlled, deftly melding two genres: biography and social history.

The thread that connects the stories in

The Lemon Table (2004) is encroaching old age and how we respond to mortality: fear, disappointment and regret. Many of the characters in this collection of stories die in the end. However, they are not as depressing or cheerless as they sound, because

Barnes enlivens his stories with dollops of wry humour.

Barnes

Barnes’ brilliant ouevre has defied pigeonholing since his first novel,

Metroland (1980), a coming-of-age satire; he debunks conventional expectations by producing both postmodern fiction that is full of linguistic naughtiness and conventional fictional devices. He is very good at dissecting “the passions and inconsistencies of the human heart, exploring the unsettling nature of love and (in)fidelity, dislocation, the quest for authenticity and truth, and the irretrievability of the past.”

Do not disregard

Barnes’s essays, however: he is also a brilliant essayist. His collected essays are well written and highly intelligent and literate, especially

Letters from London 1990-1995 (1995) and

Something to Declare: French Essays (2002); both are well worth reading.

BibliographyBARNES Julian

BibliographyBARNES Julian [1946-] Novelist, short-story writer, essayist, critic; also writes crime novels under the pseudonym

Dan Kavanagh. Born

Julian Patrick Barnes in Leicester, England.

Novels Arthur & George [2005: shortlisted for the 2005 Booker Prize for Fiction, the 2006 Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best Book (Eurasia), and the 2007 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award];

Love, etc. (2000);

England, England (1998: shortlisted for the 1998 Booker Prize for Fiction);

The Porcupine (1992);

Talking It Over (1991: winner of the French Prix Fémina);

Staring at the Sun (1986);

Flaubert’s Parrot (1984: winner of the 1985 Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize; awarded the French Prix Médicis; shortlisted for the 1984 Booker Prize for Fiction);

Before She Met Me (1982);

Metroland (1980: winner of a 1981 Somerset Maugham Award)

Stories The Lemon Table (2004);

Cross Channel (1996);

A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters (1989)

Essays The Pedant in the Kitchen (2003);

Something to Declare: French Essays (2002);

Letters from London 1990-1995 (1995)

Writing as Dan Kavanagh Going to the Dogs (1987);

Putting the Boot In (1985);

Fiddle City (1981);

Duffy (1980)

Edited/Translated In the Land of Pain /

Alphonse Daudet (2002)

Memoir Nothing to be Frightened Of (2008)